Review: Bobby Rush at the Iron Horse, Northampton. Mass. on Feb. 4, 2026

Bobby Rush may actually BE the “Hoochie Coochie Man” – as he sang-claimed Wednesday at the Iron Horse. Now 91, Rush sang his vivid story in soulful, raunchy, hard-swinging blues.

As a child in a complex, mixed-race Louisiana family, he was ripped off by an employer who joked for days about his coming payday, then handed him a Payday candy bar for a week’s work. After playing body percussion in Delta jukejoints at 14 behind a painted-on mustache, he landed at Chess Records in Chicago in 1951 when Willie Dixon offered him “Hoochie Coochie Man” to record. He declined, feeling he wasn’t yet old enough.

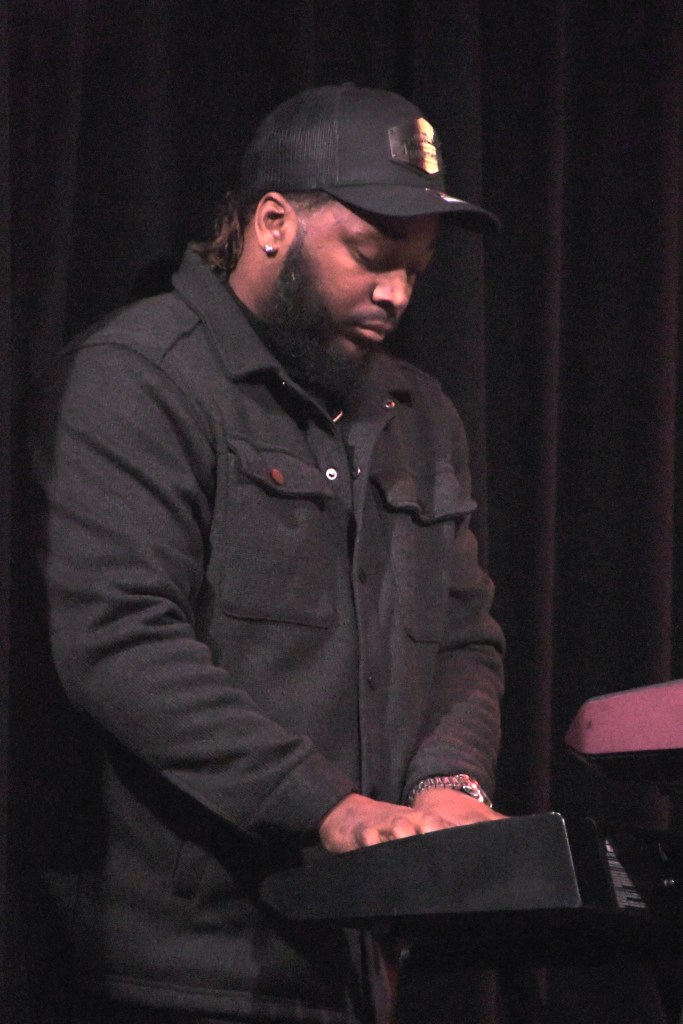

No such modesty marred Wednesday’s two set marathon show that would have exhausted a much younger performer. His band started without him, grooving on Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition.” Drummer Bruce Howard (in Rush’s band 41 years) sang lead, with guitarist Kenny Lee, bassist Arthur Cooper and a keyboardist introduced only as Robert – Rush’s son? Grandson? Then Rush took over, slim, spry and smiling under a genuine mustache in an incandescently bright jacket.

Singing strong and playing harmonica to bridge phrases and verses, he proclaimed “You So Fine,” its mildly lascivious lyric foretelling the playful sexiness spicing his blues shuffles and soul grooves. “Evil,” his next tune, overstated his intent; for him, it’s all fun; and “Big Fat Woman” described what he likes.

Here he started engaging the crowd directly, addressing front-table fans with sly suggestions the women there should be with him and not the guys who’d brought them. Rush showed sharp radar in judging how far to push these jibes, noting incredulously, “You don’t like me?” or strategically apologizing to lighten the mood.

Between leering grins in silly/sexy songs lurked the pain that relationship problems can bring, introduced by the wry torment of “I Can’t Stand it,” alternating sung and spoken sections underlining its reality. More pain flowed through “Crazy ‘Bout You” with its doomstruck refrain “You don’t care nothing in this world for me,” its sting sweetened only somewhat by tasty guitar.

Noting he’s recorded 429 songs and claiming he can sing any of 350 of them on a given night, Rush reminisced about declining to record “Hoochie Coochie Man” when offered it in 1951; then sang it hard, reclaiming it. Its bravado faded fast in “Garbage Man,” a hurt-pride lament whose umbrage also flowed through “Ride in my Automobile” to the punchline assertion song: “You’re Gonna Need a Man Like Me.”

Pride and good mood restored, Rush and band cracked up in the middle of “Same Thing” and sailed happily through “Night Fishing” and the sex comedy “G-String.”

Umbrage threaded through such autobiographical recollections as being denied a record deal because he could read the contract. But real gratitude for his collaborator Kenny Wayne Shepherd emerged as he introduced their wistful “Long Way from Home.”

As the 90-minute first set wound down, Rush widened his lyrical focus from the personal to the political, proclaiming “I’m Free” before lamenting the courtroom saga “Got Me Accused.”

Then, radiating good cheer, he crossed to the merch table to sign CDs and his book (“I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya: My American Blues Story”) – and take photos with fans.

Out of sight just long enough to swap his shiny gold jacket for a white one printed with blue butterflies, Rush re-emerged for more of the sexy, swinging same, cracking up with his band in “Bowlegged Woman, Knock-kneed Man.” He settled things down with a quick wave, his harmonica staccato over just bass drum and hi-hat as he spoke of his gratitude for living by making music.

Such serious testimony faded in a reworked version of Rush’s defiant duet with Buddy Guy, “What’s Wrong with That.” The heartbroken blues “I Lost The Best Friend I Ever Had” went deep before the juke-joint novelty numbers “Chicken Heads,” “Hey, Hey, Bobby Rush” – yes, everybody did sing along – and “Porcupine Meat.”

Bobby Rush (light jacket) and band, from left: Robert, keyboards; Kenny Lee, guitar; Bruce Howard, drums; Rush; Arthur Cooper, bass

Listening to Rush’s records later suggests his voice is still all there, and his harmonica playing, too – with a straightforward, hearty drive or sparse poignant musings on both single-key blues harps and the more versatile chromatic instrument. Things flowed smooth and simple, mostly, though Rush changed up songs’ set arrangements at times with hand-cues to simmer down, rev up or jump into a new tune altogether. Drummer Bruce Howard heard and responded instantly, leading the band in whatever new direction the boss chose.

Rush remains a complex character, with ancestors’ enslavement and oppression still sharp in his rearview mirror, overlaid with his own travails including record company abuse. He didn’t tell us about the Payday bar, or about the loss of his first wife and their three children to sickle-cell anemia. He didn’t have to; the pain rang clear when he slowed to let it emerge. But the saving grace of the blues has sustained him in a career of unprecedented duration and consistency. He may be the last legend standing of the original 1950s Chicago inventors of electric blues, but he’s too fast-moving and too much fun for solemnity to get a grip for long.