“Wasn’t Weir great?” exulted Steve Webb.

We were in Buffalo to see the Rolling Stones play Rich Stadium, third date on their 1981 Tattoo You tour; Webb to review it for the Knickerbocker News, Don Wilcock for the Troy Record and me for the Gazette. But we had lucked into tickets for the Grateful Dead the night before; walking to our car afterward, Steve had distilled that exceptional show down to a right-on observation.

The publicist on that Stones tour was the always amiable Ren Grevatt, whom I’d known for years. When I requested review tickets, he said, “I’ve got the Grateful Dead playing the War Memorial Auditorium the night before: wanna go see that, too? It’s a one-off; they’re flying from Toronto to London the next day and got a good offer, so they took it to get a payday on the East Coast before touring Europe.”

Thanks, Ren; sweet bonus.

The Dead had rehearsed before heading east and were sharper than sharp, in fine form, totally unified and full of life. Far better than the Stones the next day and thoroughly wonderful, it was one of the top three Dead shows I ever saw.

That night, September 26, 1981, rhythm guitarist and singer Bob Weir was the star.

In an asymmetrical kaleidoscopic way, one or another of them would emerge from the big flow to direct, inspire and propel.

Anybody could grab the wheel; so it wasn’t always guitar fire from Jerry Garcia, the Dead’s lead soloist, bearded icon and second-best singer. Third best when Pigpen was alive. One night, Phil Lesh’s bass would hit so hard your heartbeat would sync to it. The next, linked drums would make you dance in polyrhythms, like at a reggae show; or a soulful keyboard break would fly you to Memphis when Booker T and the MGs were still kids. That night in Buffalo, it was Weir, pushing the jams as “the best rhythm guitarist on wheels,” as Garcia once described him, singing strong and energizing the whole thing.

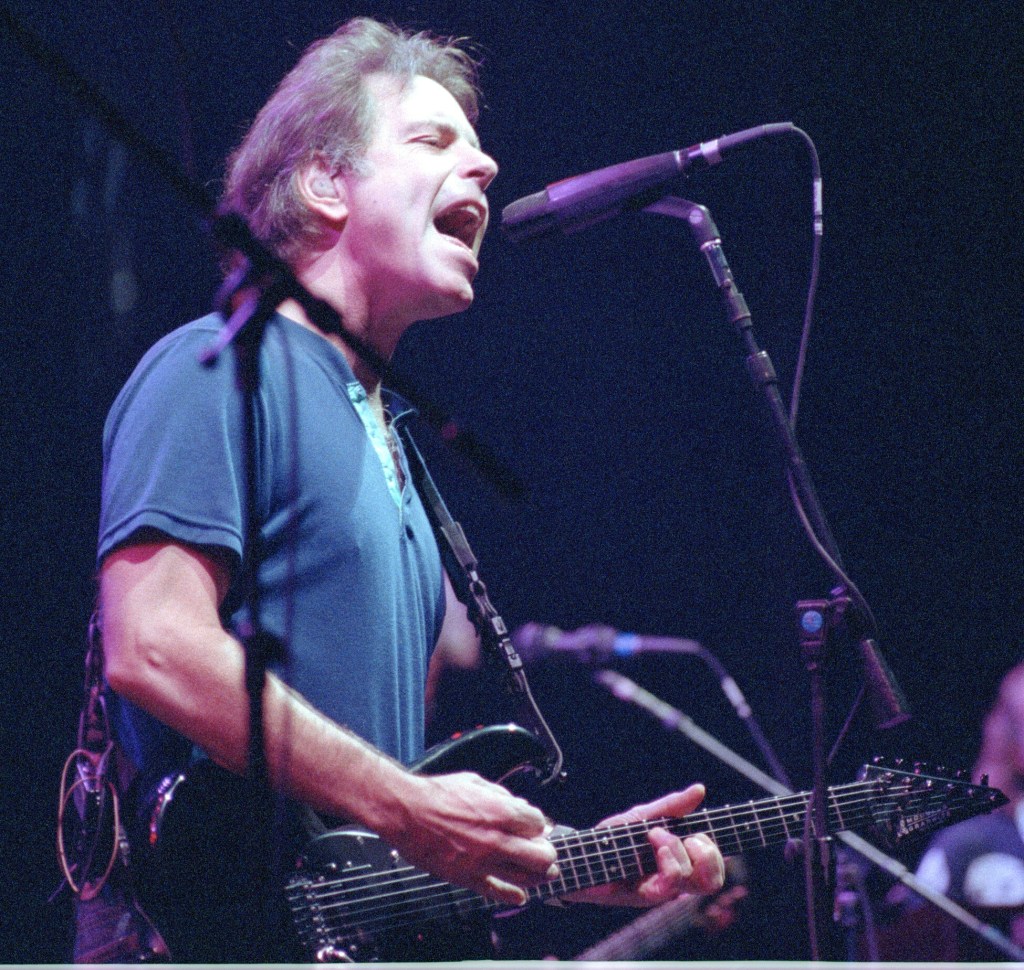

Bob Weir onstage at the Knickerbocker Arena; March 26, 1993. My photo

Obituaries have described Weir’s career with the Dead, from 1964 when he joined at 17 to Garcia’s death in 1995; acknowledging his writing of mostly upbeat songs and affection for country classics. They mention his solo album “Ace” (1972), his solo bands from the 1970s to just months ago, and echoes of the Dead including a 1997 Furthur Festival SPAC show when he joined moe. in their opening number “Cryptical Envelopment” and drove everybody crazy.

Through generous Dead publicists Robbie Taylor, Ren Grevatt and – longest-tenured and best – Dennis McNally, I saw dozens of Dead shows, more than any other band but NRBQ.

When I phone-interviewed Weir once, he introduced himself kind of formally as Robert Weir and spoke with easy open-ness of how the Dead did what they did. Then I met him briefly on the Ratdog tour-bus after a late 2007 Palace Theatre show the same night when McNally introduced me to Tom Davis (of SNL’s Al Franken and Tom Davis comedy team) over drinks before the show. I sent my Gazette review (see below) from the tour-bus, writing as Weir and the band filed aboard and Weir offered me a beer.

When I heard Saturday that Bob Weir had died, I emailed Dennis McNally:

Dennis, I have no idea what sort of connection you had with Bob Weir, but I have to believe some sense of loss follows the news of his passing. Sorry, man.

MH

Dennis wrote back:

Thank you. I rode the bus with him for four years of RatDog, and altogether we were pretty close, although less so in the last few years. But collectively, all the voices are now gone. And that’s a bit shocking…

As Dennis noted, everyone who sang in the Grateful Dead is now gone and the only original, founding member still with us is drummer Bill Kreutzmann who’d retired by the last (probably) Dead & Co. shows this spring with Weir and drummer Mickey Hart, a longtime but not founding member.

In similar news, only drummer Jaimoe (Jai Johnny Johansen) survives of the original Allman Brothers Band.

SOME EXTRAS – LOOKING BACK

THE STONES IN BUFFALO, THEN SYRACUSE

Years later, I wrote this in a letter to a friend:

The Rich Stadium show outside Buffalo was OK at best, thrilling at first for the scale and spectacle, but a let-down. When George Thorogood opened, rain was falling and folks were pissed. But the clouds parted and the sun came out when he played “Move it on Over” – then joy and exultation took over. Journey had a tough time in the middle slot, though, and left early; giving fans the finger. And the Stones were just OK: the songs were fun, but you wished they meant them more.

A few months later at the Syracuse Carrier Dome, the Stones were barely OK and the opening acts were lame. The thing didn’t reach critical mass. But, Keith did something in that show that impressed me and told me a lot about those guys. The energy was flagging in one song, so Keith went around the stage, standing face to face with every other guy there, in turn, and playing the flaming blue fuck out of his guitar, hitting the strings so damn hard and glaring at them with such “Get your shit together!” fierceness that they all did. That song went from about 30 percent power to about 95.

DEAD SET-LIST FROM THAT BUFFALO SHOW

SET 1

C.C. Rider

SET 2

Bertha >

Goin’ Down The Road Feeling Bad >

Drums >

Space >

Not Fade Away >

Morning Dew >

ENCORE

Johnny B. Goode

RATDOG CONCERT REVIEW (WRITTEN ON THE TOUR-BUS)

RatDog at the Palace on Sat., Nov. 2, 2007

By MICHAEL HOCHANADEL

ALBANY – There’s a lot of this going around: Veteran rock performers re-framing their music and making their boomer-age fans really happy. On Saturday, the night after Terry Adams introduced a new, younger mutation of NRBQ at WAMC and a few weeks after Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh & Friends detonated a tremendous show at the Glens Falls Civic Center, his former bandmate Bob Weir did the same thing at the Palace Theatre with RatDog, not so much paying tribute to the Dead’s legacy as expanding it.¶

The 90-minute first set generally moved at a deliberate piece, the capacity crowd often giving more energy to the band than the band projected from the stage. A leisurely launching pad vamp-with-solos slowly coalesced into “Terrapin Station” but it only attained significant momentum as it began to change into “All Along the Watchtower.” This wandered a bit, through a reggae episode, and reached its true instrumental majesty after Weir’s last fevered intonation “the wind began to howl” and the band did. A Tom Waits-like R&B skid-row pub crawl supplied the set’s second peak, as the band went somewhere past funk into another time zone, blasted there as much by Kenny Brooks’ tenor sax as by Steve Kimock’s Jerry Garcia-like jewel-beautiful guitar. Fans lifted off with the band, filling the aisles, dancing the furry biplane, the thunder-snake, the my-arms-don’t-respond-to-gravity. In a perfect and powerful feedback loop, the band rode the crowd’s energy, surging into “Eyes of the World” in a 20-minute, ecstatic roll that climaxed the first set.¶

After the break came an acoustic segment, paced quietly like the start of the first. “Peggy-O” and “Corrina” felt relaxed, restrained, especially when Weir reined in Kimock to toss the solo spot to Brooks. Robin Sylvester’s bass detonated “The Other One” and this venerable, can’t-miss classic had all the Dead-like essentials – swirling organ from Jeff Chimenti; a confident, questing drive flowing under the guitars; and hearty group vocals, plus Brooks darting in and out of the groove.¶

Weir was in good voice and complete, if loose, control of the band. Fans applauded his familiar tricks of building tension with repetition and eerie falsetto howls. Early on in both sets, he signaled the launch of each new episode. However, once he saw how well it was all working, he then directed traffic in a more relaxed fashion, offering clear but subtle direction via rhythm guitar riffs, sometimes insistent, sometimes soft-spoken but always effective. Playing alongside the famously intrepid Garcia cast Weir’s own playing within a long shadow, and it wasn’t always clear how well he held his own and how essential his propulsive chording was. Alongside Kimock, his playing stood out more strongly, the essential element in the band’s beats, its melodic force, its seamless flow from one tune to the next, its everything.¶