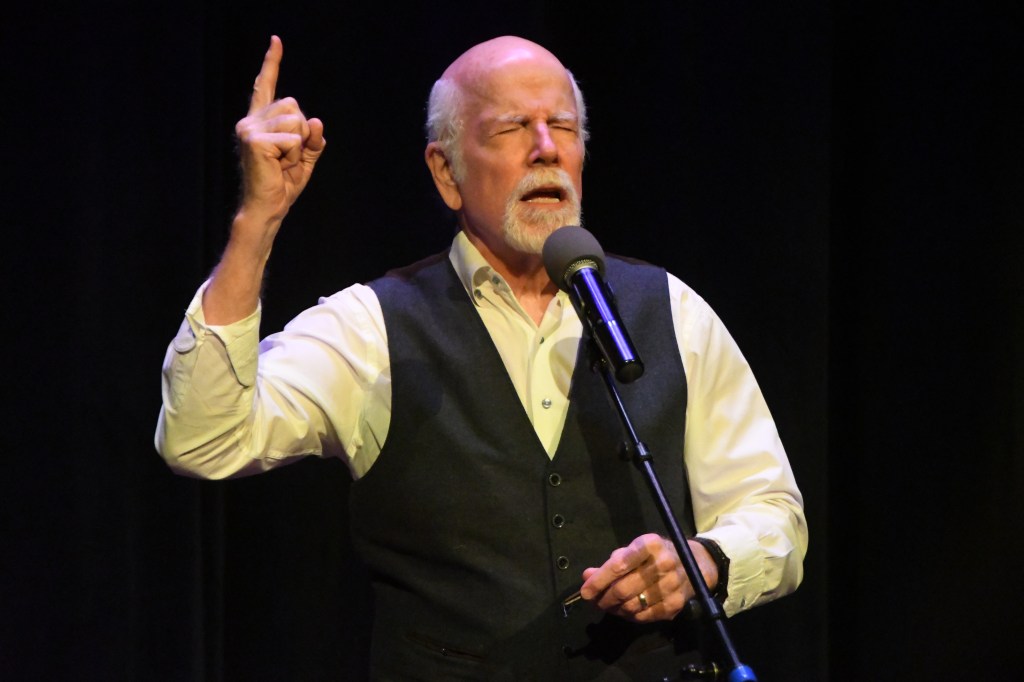

Review: John McCutcheon at the Eighth Step at Proctors GE Theatre; Friday, Nov. 14, 2025

“I’m the Bruce Springsteen of folk music,” John McCutcheon quoted a reviewer late in his Friday show at the Eighth Step in Proctors GE Theatre, wryly noting this referred to his duration onstage.

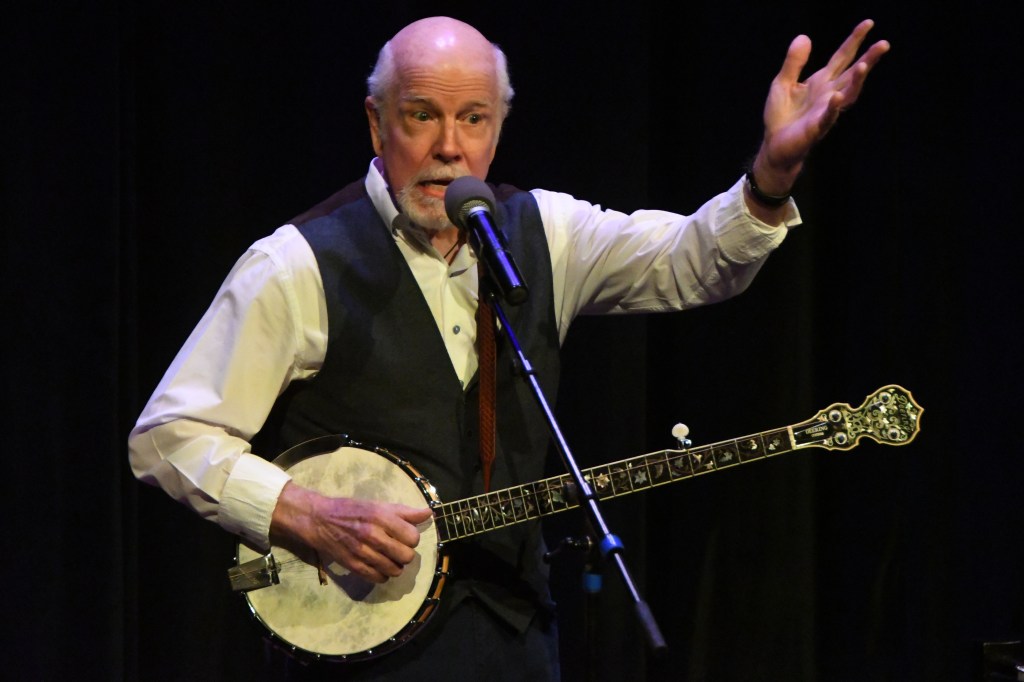

In two sets, each 70 minutes, plus intermission, McCutcheon proved as impressive in quality as quantity and earned other superlatives Friday. The Jimi Hendrix of the hammered dulcimer, a Richard Thompson-level guitarist, an ace pre-Scruggs-style banjoist, a Vassar Clements-like fiddler, a more impressive autoharp virtuoso than John Sebastian, a mellow, persuasive singer and a fun and fluent story-teller – oh, and he played expert piano, too.

Curator of song gems in the Great American Folkbook, he’s still creating, with songwriters young – Carrie Newcomer and others – and old, notably Tom Paxton, who shared the Eighth Step stage with McCutcheon three years ago and who played the Step on his farewell tour.

McCutcheon drew laughs when Step impresario Margie Rosenkranz introduced “the great John McCutcheon.” He came on joking “The GREAT John McCutcheon couldn’t be here,” in mock humility, then lit into “John Henry,” easy storytelling voice sailing over zippy banjo riffs. This vintage story-song flowed into autobiography: a hyperactive fourth grader who discovered folk music during after-school detention, whose music-making confused his family. A detail from that tale turned up later in sly sonata form echo.

He then evoked Paxton, describing their COVID-era Zoom songwriting that produced their “Christmas in the Desert,” with cars, not camels and a shift to guitar. In “Two Old To Die Young,” he wove rhymes around “old fart” and hesitated with expert comic timing after claiming his mind was intact. He later got a bit lost in some lyrics, briefly, recovering quickly and never losing momentum. “Desert” drew his first of several singalongs.

A leg fracture forestalled McCutcheon’s planned trek on the Camino de Santiago to Compostela in Spain. As he told co-writer Carrie Newcomer, “songwriters make up crap all the time,” so, without actually making the trek, their “Field of Stars” profiles four pilgrims to touching, empathetic effect. “Springfield, OH,” a Paxton co-write McCutcheon sang at the piano, poked the MAGA bear, hard and hilarious. McCutcheon stayed topical with the sympathetic “Ukrainian Now” hailing fighters’ courage. The somber waltz “One Hundred Years” mused on legacy to elegiac effect.

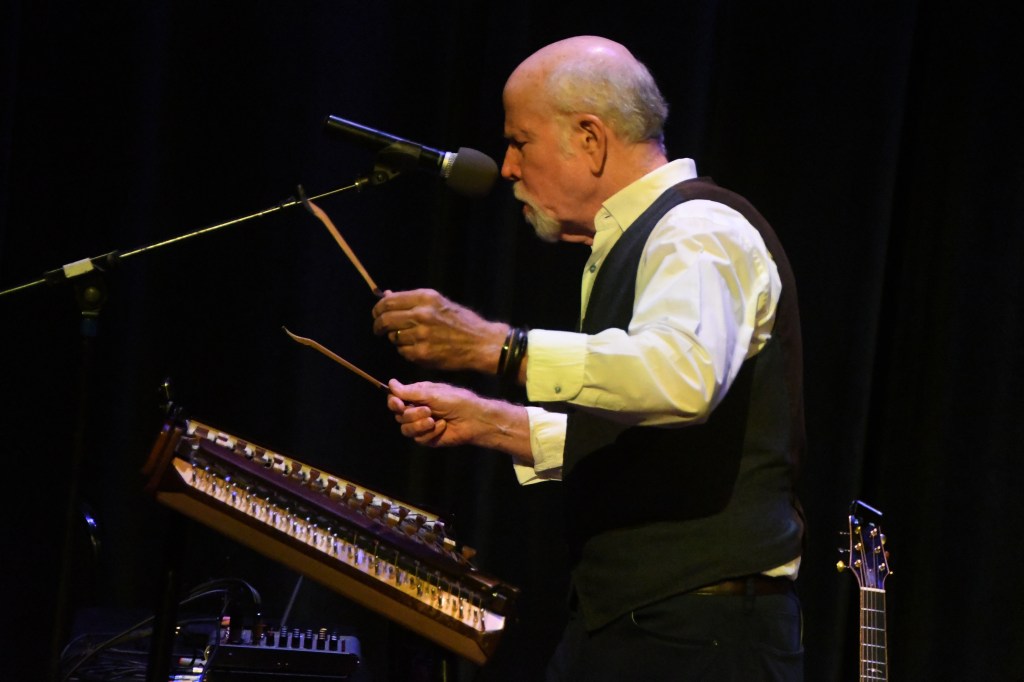

Shifting to dulcimer, McCutcheon medleyed peppy Appalachian tunes, winding up with “Niskayuna Ramble,” then stayed with the percussive stringed antique for “Letters from Joe,” mourning a soldier fallen at Normandy and echoing “Ukrainian Now.”

Another light-hearted autobiographical chat recalled his first guitar and discovering Woody Guthrie at the library by way of introducing “Pastures of Plenty” with a plenty-fine solo. After promoting his many enterprises and praising Paxton, McCutcheon sang his buddy’s superb wistful signature number “The Last Thing On My Mind” – last thing in the first set.

Catching McCutcheon’s self-deprecating tone, Rosenkranz got a laugh by introducing his second set by “seven-time Grammy loser John McCutcheon” who laughed, too. Playing slow, sad guitar, he deepened the mood with “Joe Hill’s Last Will,” somber and mournful, then lightened up and tweaked religion in “Me and Jesus,” his solo quoting “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.”

“The Machine” turned the inscription on Woody Guthrie’s guitar – “This Machine Kills Fascists” – into a challenge to continue Woody’s fight, citing the deadly Charlottesville riots. Lightening up, he identified himself as “the fiddle player” for dances and other gatherings around his Georgia home and lit into some high-energy bowing before toggling back to serious fare in “You Don’t Have to be Jewish” about school shootings. Entertaining novelty numbers on Jew’s harp closed with a marriage tale in which his father became “my own son-in-law.” A waltz on banjo wished for a world where money didn’t matter.

And this warmed up for the second set’s peak moments at hammered dulcimer – yeah, that Jimi Hendrix thing. In “Leviathan,” McCutcheon used both looping to repeat phrases and a mechanical pitch shifter that altered both the notes’ decay and their shape. As often previously, McCutcheon evoked his predecessors and mentors, but in his own innovative way, on the lovely, reverent “Wild Rose of the Mountain” based on shape-note hymns and the anthemic “Step By Step” – sizzling, stunning, strong.

Switching to autoharp, and showing as much skill on this obscure chordal zither as on everything else, McCutcheon enlisted two readers to recite the names of those anonymous air-crash victims Woody Guthrie memorialized namelessly – and that was the point – in “Deportee.” McCutcheon had discovered their names and added them to Guthrie’s lyrics; a perfect example of the folk process and subtle dig at current ICE abuses.

“Alleluia, The Great Storm Is Over” honored its writer, the recently deceased Bob Franke with its lovely melody and uplifting words of hard-won optimism. A departure-less “encore” – McCutcheon, 73, contemporary with most fans Friday, sympathized “I know what it takes to stand” – echoed that uplift in his own best-known song.

“Christmas in the Trenches” recalls a famous Christmas morning WWI truce when British and German troops met in peace to sing, share and play soccer.

In her introduction, Rosenkranz said she looked to McCutcheon to bring light in these dark times. He did, in megawatt brightness and warmth, with unmatched skill powered by a great soul full of hope.

McCutcheon met fans before the show, in an informal chat/Q&A