REVIEW – Abdullah Ibrahim Trio at The Egg Swyer Theatre; Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024

Time waits for no one, but some artists stay actively creative at ages few of us reach.

South African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim turned 90 last month and needed help climbing on and off stage Sunday. His long fingers rested on his knees as much as they worked the keyboard in his trio’s 81-minute set. He sat still at the keyboard as reeds player Cleave Guyton and bassist-cellist Noah Jackson swung Duke Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood” and John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” – dazzling duets that would largely carry the concert.

After those jazz standards, Ibrahim reached for the keys for the first time to sketch a sparse, slow melody that often recurred throughout to connect songs into a suite with brief pauses between, for applause. At times this repeating motif sounded like “Here’s That Rainy Day,” but maybe wasn’t as it changed shape. The show felt both unified by that repeating melody and a bit disjunct as Ibrahim played only sparingly and most often alone.

The show felt both unified by that repeating melody and a bit disjunct

That’s how he launched his own atmospheric “Nisa,” unaccompanied, lyrical and delicate; then he injected high arpeggios and fast bluesy runs. With no visible cue, but certain in their purpose, Jackson and Guyton rose from where they’d been waiting in chairs stage left to take over mid-song, building a bass and flute groove as Ibrahim offered comments periodically.

Then the trio, calmly business-like in black suits, briefly reverted to straight-ahead jazz tradition, putting a meditative spin on Thelonious Monk’s “Skippy” before Jackson and Guyton joined in again to continue exploring Ibrahim’s ideas through this bouncy bop.

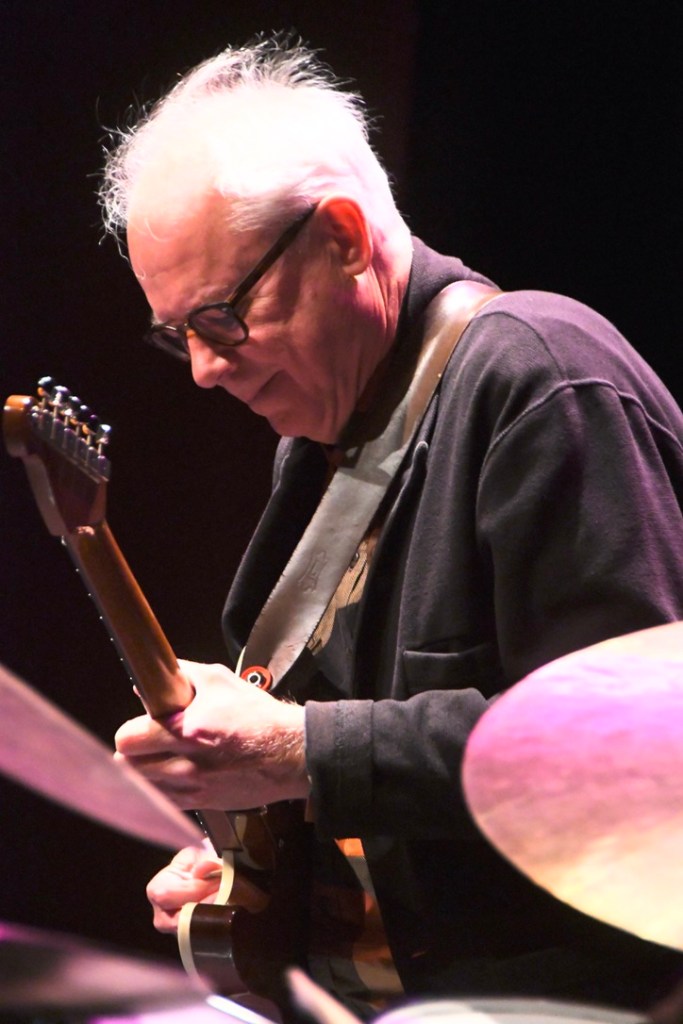

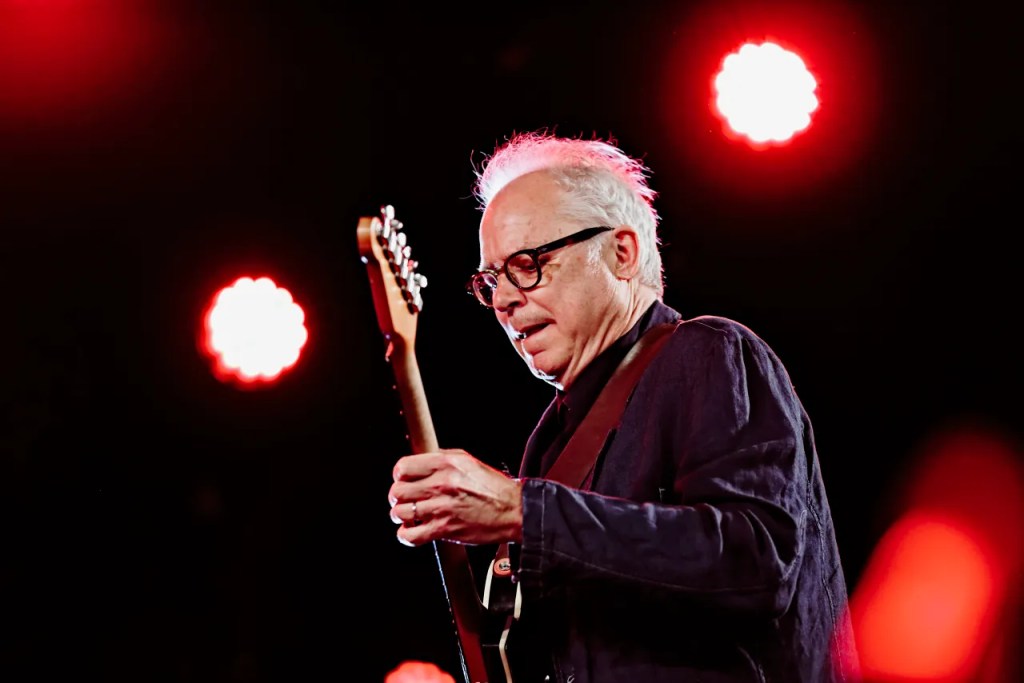

His songs and ideas played out in an episodic organic flow, often without boundaries; like Bill Frisell’s Saturday show on the same stage where things flowed into other things.

Both Ibrahim and the Guyton-Jackson duo produced striking virtuosic displays, but the fireworks always fit the songs.

They performed without mics or amplification; acoustic purity that needed no electronics for solo clarity and smooth sonic blends.

Both Ibrahim and the Guyton-Jackson duo produced striking virtuosic displays, but the fireworks always fit the songs. They returned to their original shapes in codas echoing their themes (or not…); often Ibrahim played this role.

…he seemed most at home, and most engaging, playing in mellow, almost whispery meditations; autumnal, quietly melodic.

He mostly played quietly, as in the unifying motif between tunes, but revved to impressive speed at times in the prolific style of Oscar Peterson, one of his inspirations, or off-center rhythmic explorations like Monk, another influence. The seething energy of a cross-handed passage surged with adrenaline; so did a riveting interlude of sparse low runs against jittery hyperactive repeating figures up high. These were the flashier moves of a mighty master, but he seemed most at home, and most engaging, playing in mellow, almost whispery meditations, autumnal, quietly melodic.

Guyton and Jackson served up their own fireworks, well-suited to Ibrahim’s spare arranging style that allowed lots of latitude for solo statements. Guyton was most effective on flute, his main instrument Sunday, with clarinet and super-high piccolo for spice. Jackson supplied the swagger, bass lines bustling in witty syncopation. When they flew together, though, they flew fast and far, most impressively blending cello with flute in chords they steered fearlessly through songs.

They blended this way in “Mandiss” to close, Ibrahim sitting things out until the end as Guyton and Jackson looked over at him and he held the audience’s eyes and breath to reach his index finger slowly to strike a single note as coda, farewell and thanks.

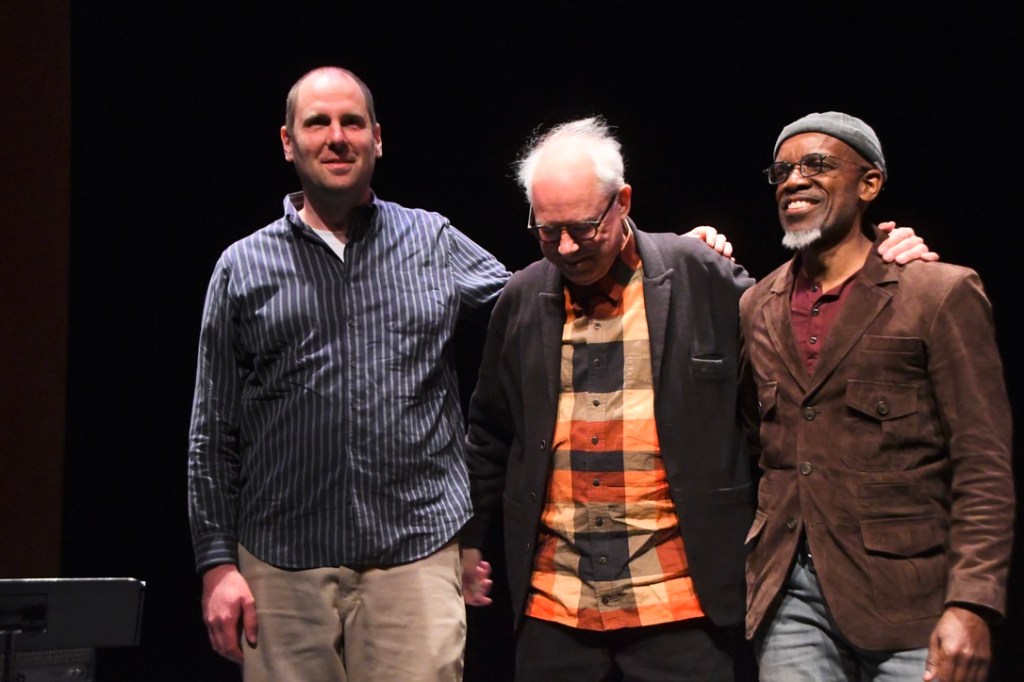

As they rose to reap the standing ovation, Ibrahim urged Guyton and Jackson forward to harvest the applause individually, hands on heart, again and again.

The Sandi Trio opened in a short set that expressed the purpose of the sponsoring Resonance Series to explore connections among world musics through a South Asian lens. At stage right, Malian Yacouba Sissoko played West African kora, center stage sat Indian violinist Arun Ramamurthy and Tim Kyper played West African percussion stage left, mainly a large gourd with sticks for busy treble runs and with the heel of his hand for emphatic booms.

The blend worked well, occasionally in the alap-and-tal form of Indian ragas with airy tentative intros coalescing into propulsive unified riffing. Sissoko and Ramamurthy alternated in leading the trio, silvery short kora notes clustering in repeating figures as Ramamurthy explored, then swapping roles while Kyper decorated it all.

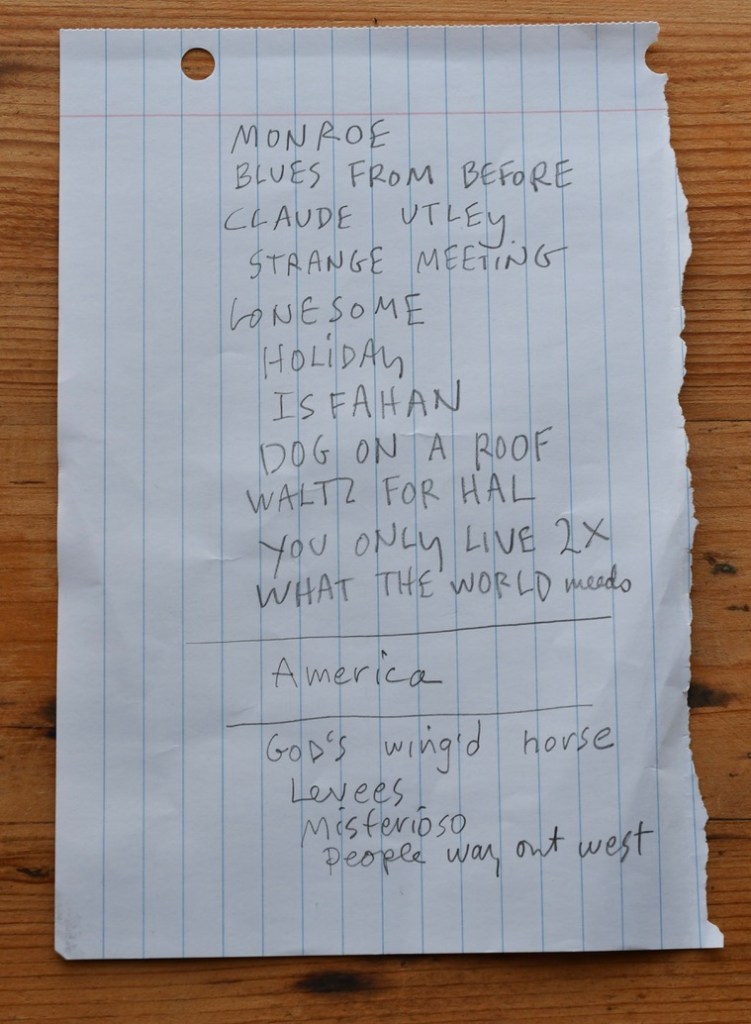

Abdulla Ibrahim Set-List

In a Sentimental Mood

Giant Steps

Nisa

Skippy

In the Evening

Peace

Water from an Ancient Well

Ishmael

Tuangura

Mandiss

Guyton kindly shared these song titles as he packed his gear after the show, paging backward through charts on his music stand, then adding, with reverence, “When (Ibrahim) soloed, he put in other stuff that we didn’t recognize.”