To the low slow voice at the used books-and-records store two counties away, I confessed: “I was in last week – I should have bought those albums.”

Quiet laugh, calm assurance; he’d heard this tune before: “I’ll put those aside for you.”

Some scenic road hours later, 1960s Duane Eddy albums filled my passenger seat. A talismanic early birthday gift to my brother Jim, they linked us to a cherished, disruptive sound – joyous rock and roll distilled to a wordless instrumental howl.

After Duane Eddy passed on April 30th, Jim Facebooked about losing his friend, the pioneering guitarist whose bold boom and simple swagger converted Jim from traditional jazz clarinetist to wild-eyed sax shouter.

Recalling how the loudspeaker outside Greulich’s Market near our Guilderland home pumped Duane Eddy songs into the parking lot – a story he’d loved telling Duane – Jim also evoked their ear-opening joy. He cherished “the low primordial sounds of a slinky echo-drenched electric guitar, accompanied by a raging, evil saxophone and a gang of demons yelping in wild abandon.” Jim celebrated he disruptive effect this gorgeous raw sound had on our staid swing-fan Catholic parents.

Years In training for the mellow melancholy of Mr. Acker Bilk’s “Stranger On The Shore” or spry strut of “Begin the Beguine” flew out the window when I started bringing home Duane Eddy 45 singles (on Jamie Records) from Apex Music Corner.

Fast forward some decades and both Jim and Duane were new to Nashville and Jim got to play with his hero. “I was immensely qualified, having learned all the aforementioned raging, evil sax parts on Duane’s records before I was shaving,” wrote Jim. He’s shown here at a later Nashville show together, grinning behind his tenor sax while Duane twangs low irresistible guitar blasts into the stratosphere.

“He invented a sound in rock ’n roll that still resonates and he did it all with such grace,” wrote Jim. “I’m ever grateful.” Duane Eddy played melodies on the guitar’s low strings or on a six-string bass; mainly working with fat hollow-body guitars jazz players favor. His innovative sound was at once tonally rude and sweet in its feel.

At a Memorial Day weekend family wedding celebration, Jim loved unwrapping those Duane Eddy albums i’d brought and told tales Duane had told him, starting with a Cavalcade of Stars tour down south.

Duane told Jim of touring at 19 on rickety buses crowded with young hitmakers sharing the same band.

When locals surrounded their bus after a Louisville concert and yelled racist insults at singer LaVerne Baker or Lloyd Price, “Dion and the Belmonts weren’t having this shit,” Jim said. “They were gonna jump off the bus and show some Bronx courtesy lessons to these (BIG expletive deleted). They had to be heavily restrained by Dick Clark and everybody because…they were all family.”

Duane told Jim of hanging out with his father at a friend’s store and gas station in Corning, New York. Duane clambered onto a stone wall and ran along the top of it, speeding up when he noticed copperhead (poisonous!) snakes crawling onto the wall behind him. “An endless string of copperheads kept coming out of the wall, a copperhead condo,” said Jim. “Snakes kept slithering out of the wall and coming after him, and he was freaking out…” until he jumped off at the end. “They were driving him along the wall…not going fast, but interested.”

Guitarists, of course, were interested in Eddy’s pre-Beatles success making instrumental rock, hoping to copperhead onto the wall behind him. TV theme composers especially favored Duane Eddy’s approach, and this worked both ways. For every “Bonanza” theme somebody else recorded, Duane covered a “Peter Gunn.”

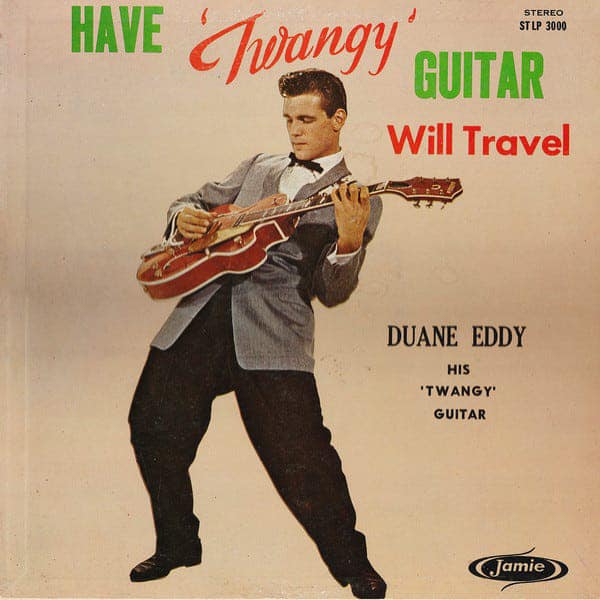

Duane’s 1958 debut album “Have Twangy Guitar Will Travel” hit number five on Billboard’s album chart and stayed on the charts for 82 weeks; he even acted in two episodes of “Have Gun – Will Travel,” the Richard Boone hired-gun Western whose title he’d borrowed. Britain’s New Musical Express (NME) voted him 1958’s World’s Number One Musical Personality, besting Elvis Presley. The Rock And Roll Hall of Fame inducted him early.

Later, when the Art of Noise remade Duane’s version of Henry Mancini’s “Peter Gunn” theme, Eddy became the only instrumentalist with top 10 hit UK singles in four different decades.

Tom Mitchell, whose Hambone record store stood in the shadow of Caffe Lena where he often played, once told me how music-timid buyers sought songs without lyrics in his shop. They gravitated to Windham Hill “new age” instrumentals to avoid triggering by lyrics with sexist or other objectionable content. Duane Eddy didn’t need words to raise alarm. His ominously low, almost menacingly resonant guitar tones, surging beats, brash saxophone hollers and massed, yelling choruses seemed plenty scary in the late 50s.

And therefore, Jim and I and multitudes loved him.

And, so, maybe, just maybe, I should have known something was up when Jim took me to the Musicians Hall of Fame on a Nashville visit a few spring-times ago – especially when Jay McDowell who ran the place came out to direct us personally into a door-side VIP parking spot.

Jay ushered us into a comfy entry lounge where a bearded, be-hatted gent and his wife rose to meet us: Duane Eddy, and wife Deed.

There’s “star-struck,” and then there’s something else, an even more intense and rarefied place where I found myself in awed silence at the Musicians Hall of Fame. I had met James Brown, Johnny Cash, Neil Young, Ray Davies of the Kinks, Joan Baez, Levon Helm, everybody in Peter Paul and Mary, all the Neville Brothers, all the Meters, everybody in Crosby Stills and Nash, everybody in the Talking Heads, everybody in the J. Geils Band, traveled for days with NRBQ…you see what I mean?

But that wasn’t this, as I realized when we all wandered into a cozy cinema where a film on the invaluable roles of session players, producers, engineers and other behind-the-scenes giants got their due. I was startled to recognize that the narrator voice in the tribute film was the same voice I heard from the man in the next seat, at my elbow: Duane Eddy.

When we wandered into an instrument-equipped alcove, a band formed, instantly. Duane grabbed a guitar; Jay a bass, and Jim sat behind the drum kit as they tuned up. Maybe they played Duane’s first hit “Movin’ ’N’ Groovin’” (1957), maybe “Rebel Rouser” – I don’t remember. But I do remember a joyous sense of privilege to be there, an audience of one.

In the exhibit halls we wandered, fans would recognize Duane and rush forward to wrap him in grateful adulation. Nobody could have been more gracious and patient, genuinely pleased to be recognized and greeted – he was the same low-key way through our three-hour lunch.

Those people who courteously swarmed him there at the Hall of Fame; they were right.

Duane Eddy, left; Jim Hoke, Jay McDowell